The summer of 2023 was the hottest summer ever recorded, according to NASA’s Goddard Institute of Space Studies (GISS) in a statement published on September 14th. Though it’s too early to be certain, this year is on track to be one of the hottest in human history.

NASA’s temperature record, the GISS Surface Temperature Analysis (GISTEMP), is a collection of temperature data that has been taken from tens of thousands of weather stations around the world since 1880. Some GISTEMP weather instruments are based on land, but they also use ships and buoys to record water surface temperatures. The assembled data can be used to quantify temperature averages and compared with any of NASA’s other previously documented records.

An analysis of the GISTEMP data indicates that the summer of 2023 was “0.41 degrees Fahrenheit (0.23 degrees Celsius) warmer than any other summer in NASA’s record and 2.1 degrees F (1.2 C) warmer than the average summer between 1951 and 1980.” Meaning that this year’s summer was exceptionally hot relative to summers in the past.

Other climate agencies have different methods for processing long-term weather data and may also be observing different ranges of time, which can lead to some variations in temperature estimates.

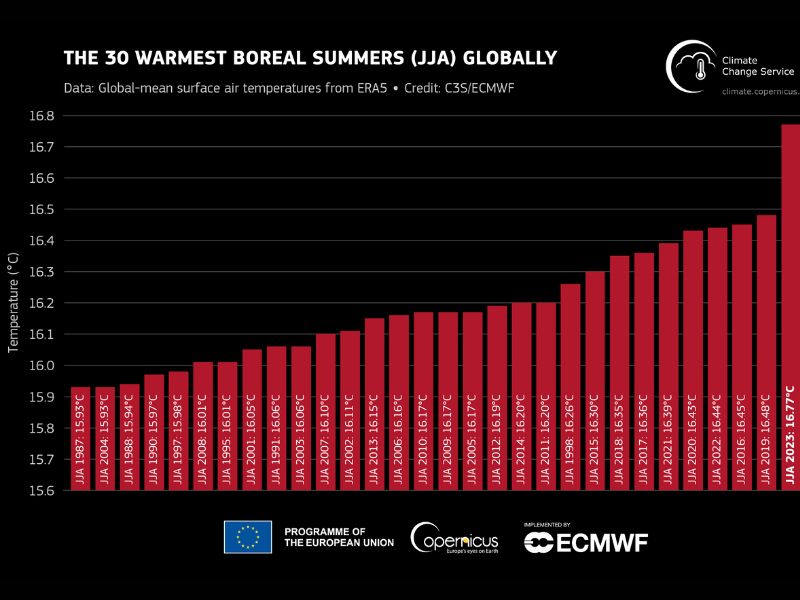

For example, the Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S) and the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF), which has been monitoring weather since 1850, also use airships and satellite data in their climate analyses. According to a report on C3S and ECMWF temperature records, the global average temperatures for June, July, and August during 2023 was 16.77 degrees Celsius (62.19 Fahrenheit), which is 0.66 degrees Celsius above the 1990 to 2020 average.

Although these two climate analyses measure different aspects of temperature and different time periods, they do have something in common: the average global temperature readings for 2023’s summer are higher than those of previous years by large margins. When compared to other summers of the past, 2023’s global temperature average is distinctly high. See the figure below.

Hottest Temperature Recorded

The chart above is an interpretation of the global-average, near-surface air temperature data for the 30 hottest boreal summers using only the months of June, July, and August, noted as “JJA”. The mean temperature for 2023 (far right bar) is extremely high compared to all the warm summers that preceded it.

The extraordinary heat of 2023’s summer coincides with several extreme weather events including record-setting heat, droughts, and wildfires that occurred across parts of Africa, Asia, Europe, and North and South America.

Canada’s wildfire season, which lasts from May to October saw much more fire activity than average very early on. It is estimated that nearly 14 million hectares have been burned so far during this year, and the fires are still hundreds of fires still burning, mostly in boreal zones. This is, without question, Canada’s worst-ever wildfire season on record, the carbon dioxide emissions of which have already doubled previous annual record, according to the European Union’s Copernicus Atmosphere Monitoring Service.

In Europe, Greece recorded its most intense wildfires since at least 2003. Data taken from Copernicus Atmosphere Monitoring Service’s (CAMS) Global Fire Assimilation System show that more than 1,000,000 tons of carbon dioxide were emitted by July 25th as a result of the fires. Statistics from the European Forest Fire Information System (EFFIS) posit that over 170,000 hectares have burned thus far.

On the island of Hawaii, a wildfire decimated the Maui town of Lahaina, burning an estimated 880 hectares. This blaze is now the deadliest fire in the United States in more than a century. Some sources have even suggested that the 2023 Maui fire is among the top 10 deadliest fires in U.S. history. 115 known deaths have been attributed to the blaze, and hundreds more are still unaccounted for.

It would be inaccurate to suggest that human-induced climate change is to blame for the severity of each of the wildfires mentioned above. In some cases, extreme fires can be the result of poor fire management strategies. However, changes in fire activity are associated with decreased humidity and heightened air temperatures, both of which are influenced by climate change. Rising temperatures increase evapotranspiration rates (the rate at which water evaporates from soils and transpires from plants). Dried-out plant matter acts as kindling during wildfires, allowing fires to ignite more easily and spread faster.

A combination of wildfires, drained water supplies, high evaporation rates, and lack of rainfall has led to a lengthy dry period (sometimes referred to as a megadrought) in Chile. Several news outlets have reported that the ongoing drought conditions in Chile have lasted for more than a decade and may be the worst drought the country has seen in 50 or 60 years. Though climate change is generally associated with increased heat and enhanced evaporation, it is not yet clear to what extent climate change is contributing to the prolonged dry period.

The role of climate change on the Horn of Africa drought conditions, however, has been quantified. An organization known as the World Weather Attribution (WWA) conducted an attribution study back in April of this year which claims that “Climate change has made events like the current drought much stronger and more likely; a conservative estimate is that such droughts have become about 100 times more likely”. The WWA team determined that the combination of low rainfall and high evapotranspiration would not have led to drought at all in a 1.2°C cooler world (they estimate that the global climate has warmed about 1.2°C by human-induced greenhouse gas emissions).

Again, increased evapotranspiration rates are an aftereffect of rising temperatures, which is why some regions are seeing plants and soils drought out much faster than usual; i.e., more severe droughts.

The WWA published another attribution study on the extreme heat in the U.S., Mexico, Southern Europe, and China this past July 2023. The study lists several temperature records that were broken, including the above 50° reading in the United States’s Death Valley on the 16th of July and the highest temperature ever recorded in Catalonia of, Spain, at 45.4 ºC on July 18th.

The WWA team’s findings indicate that “In China, it would have been about a 1 in 250-year event while maximum heat like in July 2023 would have been virtually impossible to occur in the US/Mexico region and Southern Europe if humans had not warmed the planet by burning fossil fuels. ” That is, without the influence of human-induced climate change, the extreme heat events would have been far less likely to occur.

More and more, the impact of climate change is becoming more pronounced in the intensity and likelihood of extreme weather events. If nothing else, the record-setting heat, droughts, and wildfires of summer 2023 should serve as a warning for climate action and adaptation targets for the near future.

Leave a Reply